The photo was taken near the grave of Lillian Cooper and Josephine Bedford who are buried together in Toowong Cemetery

Gai picked me up this morning around 8.30 and I got back here a bit after 5.30, feeling in a kind of stasis, wired and buggered simultaneously. I managed to feed the cat and after getting some equilibrium back started packing for my move to my next catsitting gig at Chelmer tomorrow. I've made a start and that was enough to feel up to eating and so now I'm able to write this piece.

Tomorrow is Stonewall Day and originally Pride Festival in Brisbane used to start around Stonewall Day and back in the early 90s Gai and I and the rest of the Queer Radio crew used to do a day of Queer Radio on Triple Z for Stonewall day. Sydney's Mardi Gras started as a Stonewall Day celebration in solidarity with the queer communities in California who were fighting a homophobic ballot proposition. If you check out the movie Milk you'll get the details of those struggles. And such was the power of the Stonewall myth that the Sydney cops got into the act and put on a display of police thuggery just as the New York cops did on the very first Stonewall Day back in 1969. Such is the power of myth I suppose.

When I was coming out in late 1972, Stonewall had already taken on the aura of myth. I remember as a closeted young anti-war activist Catholic Workerish hippie first hearing about Stonewall in '71 or maybe early '72 and being thrilled and excited and empowered. In 1972, Gay Liberation groups started appearing in the anti-war marches in Melbourne. In those days the symbol was the pink triangle and that presence was an impetus for me to get down and seriously work through my own issues and finally bite the bullet and come out, a fabulous radical fairy - I identified myself as an effeminist - bursting out of the chrysallis or straightjacket. I'd grown myself a beard and one of the first things I did to kick out the closet door was to shave it off - I have never regrown it. Carter Heyward aptly describes coming out as a journey without maps and that's what it felt like for me and I'm sure it must still feel like that for so very many even today.

Of course, I also realise that there are many who have no idea of what I speak when I talk about Stonewall Day. You can read the full details on Wikipedia here but I will give a brief synopsis. The Stonewall Inn was a Mafia owned bar in Christopher St Greenwich Village New York. As bars went it was a pretty downmarket affair catering mainly to the folks who were on the margins of the Greenwich Village gay scene, transvestites, young folks, especially street kids, bull dykes etc. At 1.20am on the morning of June 28 the place was raided by the cops. They thought it would be the usual routine bust rounding up a few queers and taking them back to the station. More often than not their names would be published in the newspapers. In those days in New York even the more well heeled gay bars existed on police sufferance and police raids were a risk of the time and anyone arrested would be likely to have their names published in the papers.

Rather than tell the story badly I'll quote from the acccount on Wikipedia:

The police were to transport the bar's alcohol in patrol wagons. Twenty-eight cases of beer and nineteen bottles of hard liquor were seized, but the patrol wagons had not yet arrived, so patrons were required to wait in line for about 15 minutes. Those who were not arrested were released from the front door, but they did not leave quickly as usual. Instead, they stopped outside and a crowd began to grow and watch. Within minutes, between 100 and 150 people had congregated outside, some after they were released from inside the Stonewall, and some after noticing the police cars and the crowd. Although the police forcefully pushed or kicked some patrons out of the bar, some customers released by the police performed for the crowd by posing and saluting the police in an exaggerated fashion. The crowd's applause encouraged them further: "Wrists were limp, hair was primped, and reactions to the applause were classic."

When the first patrol wagon arrived, Inspector Pine recalled that the crowd—most of whom were homosexual—had grown to at least ten times the number of people who were arrested, and they all became very quiet. Confusion over radio communication delayed the arrival of a second wagon. The police began escorting Mafia members into the first wagon, to the cheers of the bystanders. Next, regular employees were loaded into the wagon. A bystander shouted, "Gay power!", someone began singing "We Shall Overcome", and the crowd reacted with amusement and general good humor mixed with "growing and intensive hostility". An officer shoved a transvestite, who responded by hitting him on the head with her purse as the crowd began to boo. Author Edmund White, who had been passing by, recalled, "Everyone's restless, angry and high-spirited. No one has a slogan, no one even has an attitude, but something's brewing." Pennies, then beer bottles, were thrown at the wagon as a rumor spread through the crowd that patrons still inside the bar were being beaten.

A scuffle broke out when a woman in handcuffs was escorted from the door of the bar to the waiting police wagon several times. She escaped repeatedly and fought with four of the police, swearing and shouting, for about ten minutes. Described as "a typical New York butch" and "a dyke—stone butch", she had been hit on the head by an officer with a billy club for, as one witness claimed, complaining that her handcuffs were too tight.Bystanders recalled that the woman, whose identity remains unknown, sparked the crowd to fight when she looked at bystanders and shouted, "Why don't you guys do something?" After an officer picked her up and heaved her into the back of the wagon, the crowd became a mob and went "berserk": "It was at that moment that the scene became explosive".

he police tried to restrain some of the crowd, and knocked a few people down, which incited bystanders even more. Some of those handcuffed in the wagon escaped when police left them unattended (deliberately, according to some witnesses). As the crowd tried to overturn the police wagon, two police cars and the wagon—with a few slashed tires—left immediately, with Inspector Pine urging them to return as soon as possible. The commotion attracted more people who learned what was happening. Someone in the crowd declared that the bar had been raided because "they didn't pay off the cops", to which someone else yelled "Let's pay them off!" Coins sailed through the air towards the police as the crowd shouted "Pigs!" and "Faggot cops!" Beer cans were thrown and the police lashed out, dispersing some of the crowd, who found a construction site nearby with stacks of bricks. The police, outnumbered by between 500 and 600 people, grabbed several people, including folk singer Dave van Ronk—who had been attracted to the revolt from a bar two doors away from the Stonewall. Though van Ronk was not gay, he had experienced police violence when he participated in antiwar demonstrations: "As far as I was concerned, anybody who'd stand against the cops was all right with me, and that's why I stayed in.... Every time you turned around the cops were pulling some outrage or another." Ten police officers—including two policewomen—barricaded themselves, van Ronk, Howard Smith (a writer for The Village Voice), and several handcuffed detainees inside the Stonewall Inn for their own safety.Multiple accounts of the riot assert that there was no pre-existing organization or apparent cause for the demonstration; what ensued was spontaneous. Michael Fader explained,

We all had a collective feeling like we'd had enough of this kind of shit. It wasn't anything tangible anybody said to anyone else, it was just kind of like everything over the years had come to a head on that one particular night in the one particular place, and it was not an organized demonstration.... Everyone in the crowd felt that we were never going to go back. It was like the last straw. It was time to reclaim something that had always been taken from us.... All kinds of people, all different reasons, but mostly it was total outrage, anger, sorrow, everything combined, and everything just kind of ran its course. It was the police who were doing most of the destruction. We were really trying to get back in and break free. And we felt that we had freedom at last, or freedom to at least show that we demanded freedom. We weren't going to be walking meekly in the night and letting them shove us around—it's like standing your ground for the first time and in a really strong way, and that's what caught the police by surprise. There was something in the air, freedom a long time overdue, and we're going to fight for it. It took different forms, but the bottom line was, we weren't going to go away. And we didn't.

Garbage cans, garbage, bottles, rocks, and bricks were hurled at the building, breaking the windows. Witnesses attest that "flame queens", hustlers, and gay "street kids"—the most outcast people in the gay community—were responsible for the first volley of projectiles, as well as the uprooting of a parking meter used as a battering ram on the doors of the Stonewall Inn. Sylvia (Ray) Rivera, who was in full drag and had been in the Stonewall during the raid, remembered: "You've been treating us like shit all these years? Uh-uh. Now it's our turn!... It was one of the greatest moments in my life." The mob lit garbage on fire and stuffed it through the broken windows as the police grabbed a fire hose. Because it had no water pressure, the hose was ineffective in dispersing the crowd, and seemed only to encourage them. When demonstrators broke through the windows—which had been covered by plywood by the bar owners to deter the police from raiding the bar—the police inside unholstered their pistols. The doors flew open and officers pointed their weapons at the angry crowd, threatening to shoot. The Village Voice writer Howard Smith, in the bar with the police, took a wrench from the bar and stuffed it in his pants, unsure if he might have to use it against the mob or the police. He watched someone squirt lighter fluid into the bar; as it was lit and the police took aim, sirens were heard and fire trucks arrived. The onslaught had lasted 45 minutes.

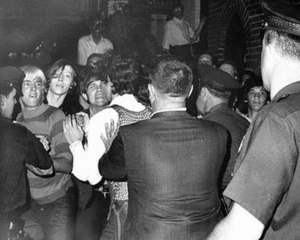

This photograph appeared in the front page of The New York Daily News on Sunday, June 29, 1969, showing the "street kids" who were the first to fight with the police.

The Tactical Police Force (TPF) of the New York City Police Department arrived to free the police trapped inside the Stonewall. One officer's eye was cut, and a few others were bruised from being struck by flying debris. Bob Kohler, who was walking his dog by the Stonewall that night, saw the TPF arrive: "I had been in enough riots to know the fun was over.... The cops were totally humiliated. This never, ever happened. They were angrier than I guess they had ever been, because everybody else had rioted ... but the fairies were not supposed to riot ... no group had ever forced cops to retreat before, so the anger was just enormous. I mean, they wanted to kill." With larger numbers, police detained anyone they could and put them in patrol wagons to go to jail, though Inspector Pine recalled, "Fights erupted with the transvestites, who wouldn't go into the patrol wagon". His recollection was corroborated by another witness across the street who said, "All I could see about who was fighting was that it was transvestites and they were fighting furiously".

The TPF formed a phalanx and attempted to clear the streets by marching slowly and pushing the crowd back. The mob openly mocked the police. The crowd cheered, started impromptu kick lines, and sang to the tune of The Howdy Doody Show theme song: "We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We don't wear underwear/ We show our pubic hairs". Lucian Truscott reported in The Village Voice: "A stagnant situation there brought on some gay tomfoolery in the form of a chorus line facing the line of helmeted and club-carrying cops. Just as the line got into a full kick routine, the TPF advanced again and cleared the crowd of screaming gay power[-]ites down Christopher to Seventh Avenue." One participant who had been in the Stonewall during the raid recalled, "The police rushed us, and that's when I realized this is not a good thing to do, because they got me in the back with a night stick". Another account stated, "I just can't ever get that one sight out of my mind. The cops with the [nightsticks] and the kick line on the other side. It was the most amazing thing.... And all the sudden that kick line, which I guess was a spoof on the machismo ... I think that's when I felt rage. Because people were getting smashed with bats. And for what? A kick line."

By 4:00 in the morning the streets had nearly been cleared. Many people sat on stoops or gathered nearby in Christopher Park throughout the morning, dazed in disbelief at what had transpired. Many witnesses remembered the surreal and eerie quiet that descended upon Christopher Street, though there continued to be "electricity in the air". One commented: "There was a certain beauty in the aftermath of the riot.... It was obvious, at least to me, that a lot of people really were gay and, you know, this was our street." Thirteen people had been arrested. Some in the crowd were hospitalized, and four police officers were injured. Almost everything in the Stonewall Inn was broken. Inspector Pine had intended to close and dismantle the Stonewall Inn that night. Pay telephones, toilets, mirrors, jukeboxes, and cigarette machines were all smashed, possibly in the riot and possibly by the police.

More riots broke out in the Village over the next week and from this time of public resistance to the cops and powers that be a new militant gay identity was born and in those early days gay was a term to cover everyone, conveying a politics as much as anything else, in ways reminiscent of how queer took off especially here in Brisbane in the early 90s as denoting a politics as well as an identity.

The significance of Stonewall was that it was about resistance and it took on a mythological quality. Many people think there was nothing before Stonewall. There is a history of organising and struggle by LGBT people going back over 150 years especially in Europe and even in the US, in 1968 the queers in LA had felt empowered enough to establish the Pink Panthers to protect themselves against anti-queer violence. But Stonewall did mark the first documented spontaneous uprising in the face of an enterenchd homophobic system. The fairies were fighting back, something that wasn't supposed to happen.

Back in my undergrad days, I wrote a study of the utopian relgious dimension of the old Gay Liberation movement and in that long essay I wrote an account of the Stonewall riots. Part way in I noticed I had shifted unconsciously to present tense. I realised I had been taken over by the power of the myth but instead of correcting myself I left it unchanged as an example of mythic power. Sadly nowadays, there is an attitude that there is something wrong with myth. Back last century the German theologian and biblical scholar, Rudolf Bultmann, called for the demythologisation of Christianity. Modern 'man' had grown up and mythology was no longer relevant in the modern rational world of the 20th century. Myth is unreal, does not reflect the real world.

I regard myths as stories that convey power and meaning (for good or ill - the Australian ANZAC myth works for ill). A myth may or may not be based on real events. The Stonewall story is a classic example of a myth based on real events. But the Stonewall story has always functioned as one that conveys power, empowers people, and gives meaning. Even forty years later the story has a power and I think in these days of appropriation and almost assimilation of LGBT folk into the heteronormative system, at least in our Western societies, it might also serve as a dangerous memory. The Stonewall story I received came in a package that was liberationist, anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchal, anti-racist and anti-war. I think those elements should be reclaimed. Rather than gays and lesbians in the military, lets abolish the military; rather than same-sex marriage lets abolish marriage and develop something better (and there is a very worthy history of marriage resistance going back centuries).

A myth's power also lies in its ability to provide a point of connection, of significance for people's personal stories, personal myths. In my case I have a very real point of connection, one that I've never quite been able to put into words but nevertheless makes me feel personally linked to those events in Christopher St on the other side of the world. On the eve of the Stonewall riots here in Brisbane June 27 in the evening, which in New York would have been the early hours of 27 June, I was being operated on for what would turn out to be testicular cancer (and yes it was removed). It was a week before I turned 17 and I was discharged from the hospital the day before my 17th birthday and I was told that I had cancer, I think the day before I was discharged. But by then I already knew. Believe it or not I didn't really know about astrology back then [1]; I had been talking with another patient about my coming birthday and they made the comment "Oh, Cancer" and at that point I knew what I had (the body always knows). So when the doctor told me the next day, it was almost like a sense of relief swept over me. It was confirmation. Back then testicular cancer was a major killer of males my age. No one told me that, I found that out later. But I was told my health would be monitored for the next five years but part of me knew that there was a good chance that I might not be around in five years time (and I found out later on that a good many people feared that might be the case). As a highly closeted Catholic gay teenager the fact of cancer, and testicular cancer to boot, came as quite a jolt to the system. A couple of years later I found out about Stonewall and realised the importance of the dates. By that stage I had already taken the path of so many young queer folk and fled Brisbane to go to Melbourne, in my case, to join the revolution. I saw myself as somehow marked by Stonewall in what I realise now might be termed a shamanic way - I didn't really know anything about shamanism then. And I still don't really have the words to decribe how the confluence of dates resonated with me. But that resonance set me on the journey without maps, I hesitate to say a vocation. But maybe vocation is the word because I understood myself as being called to do something, to contribute to what would be the unfolding, still unfolding struggle to tear down the disciplines of homophobia, kick down that closet door for all time. And if there was a vocation for me it was to tackle the beast in its lair, religion. It took me many years before I reached the point where I could follow that call to tackle the religious roots of homophobia. And over all those years without any map, there have been plenty of times when I have lost my way. And one thing I think is important is to reassure people that, hey there is no shame in getting lost along the way, there ain't no maps; we are merely tracing outlines that might one day be maps for people a long way down the track. Hence we all need to be gentle with ourselves and with each other.

So happy Stonewall Day everybody. Here's to those fabulous fairies and dykes and trannies who one night in June 40 years ago decided to fight back!

"We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We don't wear underwear/ We show our pubic hairs".

[1] Astrologically, at the time of the cancer I was experiencing a solar arc progression of Mars squaring my natal Pluto. In 1991, I had another life threatening medical emergency, one that propelled me to university the following year. This time transiting Pluto was squaring its natal position.